By guest blogger Robyn Aston, volunteer with the River Otter Ecology Project and member of the Otter Specialist Group of the IUCN

May 27, 2015

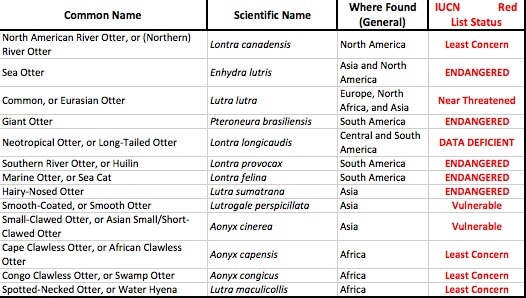

Currently, there are thirteen species of otters worldwide. All of them are monitored (along with most of the plant and animal species on the planet) by the International Union for the Conservation of Nature (IUCN).

Of the thirteen species, five are “Endangered,” one “Data Deficient [not enough information],” one is “Near Threatened,” two are “Vulnerable,” and four are deemed “Least Concern.”

In California we are fortunate to have two species which, although similar in many ways, are each quite different from the other: the Sea Otter (Enhydra lutris), listed as “Endangered”; and the North American River Otter (Lontra canadensis), listed as “Least Concern.”

“Least Concern,” is not as mild a situation as it might seem. While those species are not on the verge of extinction, they are not necessarily safe from loss of habitat and food availability.

Looking at our North American River Otter, when the Europeans first set foot on North America, they were as widely present as the beaver (Castor canadensis) and the Timber wolf (Canis lupus). All could be found throughout the ten Provinces and three Territories of Canada, and the 49 US States, although there were some areas of exception.

By 1977, primarily because of hunting (for pelts), water pollution from agriculture, mining, and industry, the destruction of habitat and the encroachment of man, the historical range of the River otter continent-wide, had been reduced by up to 30%, with many States indicating total extirpation of the species. Their range reduction in California was closer to 50%.

In 1962, California passed a ban on the hunting of all species of otter (the Sea Otter was all but gone here), and in 1972, the federal Clean Water Act was mandated (and constantly under attack by select Senate Republicans). The result? Not only are we seeing the return of the River otter to many areas, but also that it is possible for humans and otters, to co-exist in the same areas.

In some provinces and states, major otter re-introduction projects are underway with much success. The otters are thriving—the water is relatively clean, the populations of fish are good. Unfortunately, in some states, because they are seen to be doing well, fur-trapping has been re-instituted [virtually all of the skins are exported].

Although in the United States we have been doing a reasonably good job assisting River Otters to make a comeback, they are still far from their historical distribution—in California, that would be from the San Luis Obispo watershed north. There are still local, national, and international challenges ahead including: awareness; repairing and maintaining our environment; climate change.

Because they are top predators [at the pinnacle their food chain], and utilise both water, and land environments, otters are ideal environmental indicators—canaries in the mine, so-to-speak. Any contaminants that enter their food web become more concentrated with each step, resulting in the highest concentration at the top. They are among the first species to disappear from a polluted watershed.

This applies to every species of otter, in every nation. Each, though not necessarily “Endangered,” is so close to the edge. Numbers are down. Distribution is down. Every otter species is of particular concern.

Further Reading:

- Allen, D (2010) Otter. Reaktion Books, London, UK.

- Dillon, R (1975) Siskiyou Trail: The Hudson’s Bay Fur Company Route to California. McGraw-Hill, New York, NY, USA.

- Feldhammer, GA, Thompson, BC, and Chapman, JA (eds.) (2003) Wild Mammals of North America: Biology, Management, and Conservation. Second Edition. Johns Hopkins University Press, Baltimore, MD, USA.

- Kruuk, H (2006) Otter: Ecology, Behaviour, and Conservation. Oxford University Press, Oxford, UK.

- Yoxon, P, and Yoxon, GM (2014) Otters of the World. Whittles Publishing, Caithness, Scotland, UK.