By guest blogger Beth Cataldo

December 10, 2017

Beth is a certified California Naturalist, Winter Wildlife Docent at Point Reyes National Seashore and a BeachWatch volunteer at the Farallones Marine Sanctuary Association. She began volunteering with ROEP in June 2017.

In 2012, I ventured out to Sutro Baths to see a San Francisco celebrity. With his thick dark hair, slender, streamlined body and expert swimming skills, he was an overnight media sensation. Charismatic? Check. Quirky? Check. Mysterious? Yes. I wanted to get a good look at Sutro Sam — a wild North American river otter. No one had seen anything like him in San Francisco for as long as anyone could remember.

Courtesy of sfwildlife.com

North American river otters once lived throughout Northern and Central California in marshes, bays, rivers and lakes but by the 1950s, their numbers had been greatly reduced. The most recent California Fish and Wildlife range map, from 1995, shows a blank for river otters in much of the San Francisco Bay Area, including Marin and the East Bay. While Sutro Sam still wasn’t officially on the map, his return, as part of a general Coastal and Bay recovery, was testimony to our watershed-restoration efforts. His story came to mind when I started volunteering for the River Otter Ecology Project (ROEP) this past June. I was looking forward not only to sightings of these charismatic mammals but also to helping with the work that would put them back on the official map and help us understand their place in local ecosystems.

Belinda Rain/Documerica, EPA

A Stinky Mess

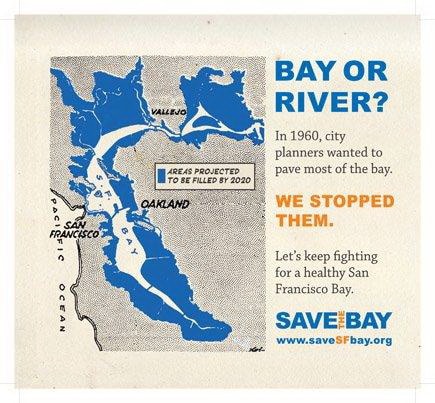

Why did the river otters disappear in the first place? It was most likely primarily because of loss of wetlands, trapping and pollution. Hardcore pollution began in the 1850s, when sediment from the Gold Rush flowed into the Bay. In the 1950s and 60s, people would hold their noses as they crossed the Bay Bridge, trying to block out the stench of raw sewage and toxic trash that were dumped directly into the water. People describe watching flames on the bay at night as the garbage-dump employees set the trash on fire. To increase industrial production, parts of the bay were filled in along the waterfront. In 1959, the United States Army Corps of Engineers warned that the bay would turn into a river by 2020 if the filling trends continued.

They successfully lobbied for a new state agency, the Bay Conservation and Development Commission (BCDC), establishing the first coastal protection agency in the United States, which put a moratorium on filling in the Bay and closed more than 30 city garbage dump sites. Other groups followed, including Citizens Committee to Complete the Refuge, San Francisco Estuary Partnership and the San Francisco Bay Joint Venture. Most importantly, people were awakened by these efforts and became involved in deciding the future of the Bay. The year was 1961, and that same year river otters were granted protected status by California Fish and Game, and could no longer be legally hunted or trapped.

Perhaps Sutro Sam showed up in San Francisco to celebrate the 40th anniversary of the Clean Water Act, which in 1972 regulated the discharge of pollutants into the nation’s surface waters. Part of the legislation focused on minimizing the destruction of wetlands and waterways which, in turn, protected water quality and provided habitat for fish and wildlife. Federal, state and local projects also were initiated to begin cleaning up and restoring local marshes and wetlands. Localized projects continue, like the Giacomini Wetlands Project in southern Tomales Bay and the Rodeo Lagoon Wetlands Project in the Marin Headlands. While going out on site visits with the River Otter Ecology Project, I’ve spotted river otters in both these areas. Since they are top predators, they have benefited from these restoration efforts, which create healthier conditions for their food – chiefly fish, crayfish, crabs and birds.

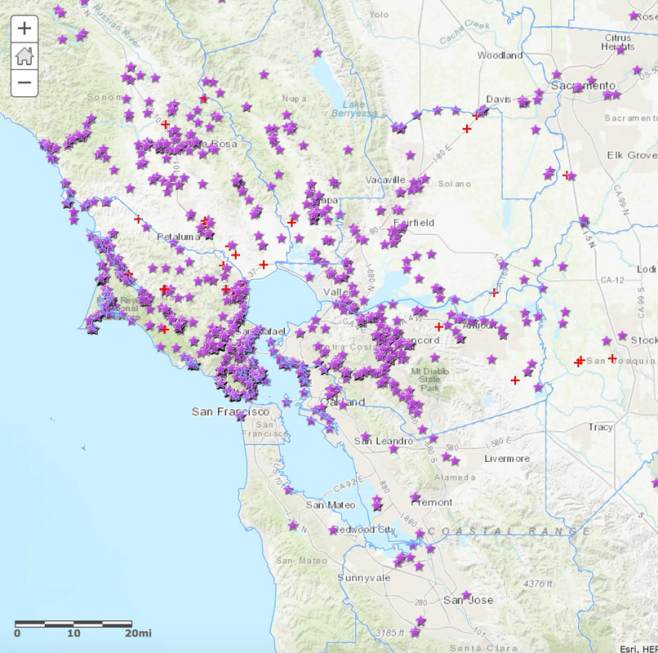

Megan Isadore, a long-time conservationist and one of the founders of the River Otter Ecology project, had her first good look at the playful river otters on Lagunitas Creek in Marin in 2005. Early on a cold winter morning, she watched as four otters swam, hunting crayfish and chirping back and forth until they came out onto a sandbar and groomed themselves. She knew that if she was seeing them in Marin, they must be elsewhere. Yet no one was tracking them and, officially, they didn’t exist in that range. She and her cofounders agreed that these charismatic, sentinel mammals would make ideal ambassadors for watershed conservation and wetland restoration. That morning, these otters were more than just a mother and pups out hunting.She, Paola Bouley and Terence Carroll founded the River Otter Ecology Project in 2012 to investigate the recovery of the river otter population in the SF Bay Area in order to inform wetland restoration and support watershed conservation. One of their first undertakings was Otter Spotter, a community-science project that tracks and documents the river otter recovery through individuals reporting otter sightings on their website. Since 2012, Otter Spotter has plotted 2,300+ sightings from all the Bay Area counties with the exception of San Mateo.

ROEP data. Red crosses are otter mortalities. Almost all are car strikes.

CDF&W Range Map, River Otters with proposed changes

A Story of Resilience

In September 2017, nearly five years after Otter Spotter logged its first sighting (and when Sutro Sam first appeared), the California Department of Fish and Wildlife has agreed to fill in the official range map to reflect Otter Spotter sightings (the blue area on the map at left).The range map provides information on otter presence for agencies responsible for oil and other spill responses. It can also help illustrate the value of environmental restoration, important for public appreciation of any conservation effort, especially with the recent threats to end funding to the Environmental Protection Agency and proposed changes to the Endangered Species Act. I’ve heard many people state that it is too late to mitigate climate change, but this story of recovery should not be lost on us as we look at bold moves to adapt to the changing world.

On that day when I went looking for Sutro Sam, I waited in the parking lot for almost an hour. I had never seen a river otter in the wild so I was willing to hang out and watch the pelicans pass over as the fog drifted in. Late in the afternoon, I spotted him through binoculars swimming in Sutro Baths, inside the dilapidated concrete remnants of a structure that burned down in 1966.

Otters aren’t the only ones making a homecoming in San Francisco Bay. Humpback whales, pacific harbor porpoises and even great white sharks have been spotted, sometimes in large numbers, since 2009.

We may never know where Sutro Sam came from or where he went. It took more than fifty years of environmental changes for him to find his way to San Francisco: More than half a human lifetime and a few generations of river otters. But for the 4.5 billion-year-old planet, that’s just a breath. Give wildlife enough food and a clean place to live, and it will return. As Jane Goodall likes to say, “Nature can win if we give her a chance.”